In this article

Building a BitTorrent Client

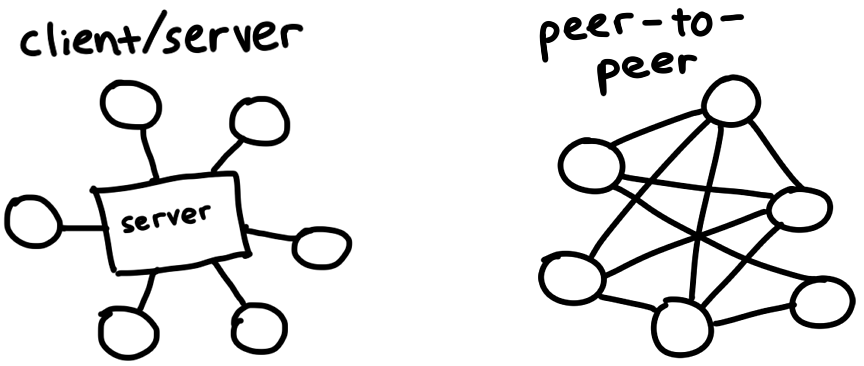

BitTorrent is a protocol for downloading and distributing files across the Internet. In contrast with the traditional client/server relationship, in which downloaders connect to a central server (for example: watching a movie on Netflix, or loading the web page you’re reading now), participants in the BitTorrent network, called peers, download pieces of files from each other—this is what makes it a peer-to-peer protocol. In this article we will investigate how this works, and build our own client that can find peers and exchange data between them.

The protocol evolved organically over the past 20 years, and various people and organizations added extensions for features like encryption, private torrents, and new ways of finding peers. We’ll be implementing the original spec from 2001 to keep this a weekend-sized project.

I’ll be using a Debian ISO file as my guinea pig because it’s big, but not huge, at 350MB. As a popular Linux distribution, there will be lots of fast and cooperative peers for us to connect to. And we’ll avoid the legal and ethical issues related to downloading pirated content.

Finding peers

Here’s a problem: we want to download a file with BitTorrent, but it’s a peer-to-peer protocol and we have no idea where to find peers to download it from. This is a lot like moving to a new city and trying to make friends—maybe we’ll hit up a local pub or a meetup group! Centralized locations like these are the big idea behind trackers, which are central servers that introduce peers to each other. They’re just web servers running over HTTP, and you can find Debian’s at http://bttracker.debian.org:6969/.

![]()

Of course, these central servers are liable to get raided by the feds if they facilitate peers exchanging illegal content. You may remember reading about trackers like TorrentSpy, Popcorn Time, and Kickass Torrents getting seized and shut down. New methods cut out the middleman by making even peer discovery a distributed process. We won’t be implementing them, but if you’re interested, some terms you can research are DHT, PEX, and magnet links.

Parsing a .torrent file

A .torrent file describes the contents of a torrentable file and information for connecting to a tracker. It’s all we need in order to kickstart the process of downloading a torrent. Debian’s .torrent file looks like this:

d8:announce41:http://bttracker.debian.org:6969/announce7:comment35:"Debian CD from cdimage.debian.org"13:creation datei1573903810e9:httpseedsl145:https://cdimage.debian.org/cdimage/release/10.2.0//srv/cdbuilder.debian.org/dst/deb-cd/weekly-builds/amd64/iso-cd/debian-10.2.0-amd64-netinst.iso145:https://cdimage.debian.org/cdimage/archive/10.2.0//srv/cdbuilder.debian.org/dst/deb-cd/weekly-builds/amd64/iso-cd/debian-10.2.0-amd64-netinst.isoe4:infod6:lengthi351272960e4:name31:debian-10.2.0-amd64-netinst.iso12:piece lengthi262144e6:pieces26800:� ����PS�^�� (binary blob of the hashes of each piece)eeThat mess is encoded in a format called Bencode (pronounced bee-encode), and we’ll need to decode it.

Bencode can encode roughly the same types of structures as JSON—strings, integers, lists, and dictionaries. Bencoded data is not as human-readable/writable as JSON, but it can efficiently handle binary data and it’s really simple to parse from a stream. Strings come with a length prefix, and look like 4:spam. Integers go between start and end markers, so 7 would encode to i7e. Lists and dictionaries work in a similar way: l4:spami7ee represents ['spam', 7], while d4:spami7ee means {spam: 7}.

In a prettier format, our .torrent file looks like this:

d

8:announce

41:http://bttracker.debian.org:6969/announce

7:comment

35:"Debian CD from cdimage.debian.org"

13:creation date

i1573903810e

4:info

d

6:length

i351272960e

4:name

31:debian-10.2.0-amd64-netinst.iso

12:piece length

i262144e

6:pieces

26800:� ����PS�^�� (binary blob of the hashes of each piece)

e

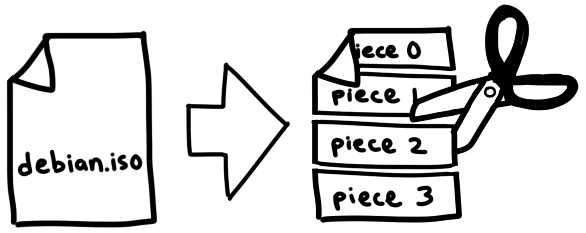

eIn this file, we can spot the URL of the tracker, the creation date (as a Unix timestamp), the name and size of the file, and a big binary blob containing the SHA-1 hashes of each piece, which are equally-sized parts of the file we want to download. The exact size of a piece varies between torrents, but they are usually somewhere between 256KB and 1MB. This means that a large file might be made up of thousands of pieces. We’ll download these pieces from our peers, check them against the hashes from our torrent file, assemble them together, and boom, we’ve got a file!

This mechanism allows us to verify the integrity of each piece as we go. It makes BitTorrent resistant to accidental corruption or intentional torrent poisoning. Unless an attacker is capable of breaking SHA-1 with a preimage attack, we will get exactly the content we asked for.

It would be really fun to write a bencode parser, but parsing isn’t our focus today. But I found Fredrik Lundh’s 50 line parser to be especially illuminating. For this project, I used github.com/jackpal/bencode-go:

import (

"github.com/jackpal/bencode-go"

)

type bencodeInfo struct {

Pieces string `bencode:"pieces"`

PieceLength int `bencode:"piece length"`

Length int `bencode:"length"`

Name string `bencode:"name"`

}

type bencodeTorrent struct {

Announce string `bencode:"announce"`

Info bencodeInfo `bencode:"info"`

}

// Open parses a torrent file

func Open(r io.Reader) (*bencodeTorrent, error) {

bto := bencodeTorrent{}

err := bencode.Unmarshal(r, &bto)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &bto, nil

}Because I like to keep my structures relatively flat, and I like to keep my application structs separate from my serialization structs, I exported a different, flatter struct named TorrentFile and wrote a few helper functions to convert between the two.

Notably, I split pieces (previously a string) into a slice of hashes (each [20]byte) so that I can easily access individual hashes later. I also computed the SHA-1 hash of the entire bencoded info dict (the one which contained the name, size, and piece hashes). We know this as the infohash and it uniquely identifies files when we talk to trackers and peers. More on this later.

type TorrentFile struct {

Announce string

InfoHash [20]byte

PieceHashes [][20]byte

PieceLength int

Length int

Name string

}

func (bto *bencodeTorrent) toTorrentFile() (*TorrentFile, error) {

// ...

}Retrieving peers from the tracker

Now that we have information about the file and its tracker, let’s talk to the tracker to announce our presence as a peer and to retrieve a list of other peers. We just need to make a GET request to the announce URL supplied in the .torrent file, with a few query parameters:

func (t *TorrentFile) buildTrackerURL(peerID [20]byte, port uint16) (string, error) {

base, err := url.Parse(t.Announce)

if err != nil {

return "", err

}

params := url.Values{

"info_hash": []string{string(t.InfoHash[:])},

"peer_id": []string{string(peerID[:])},

"port": []string{strconv.Itoa(int(Port))},

"uploaded": []string{"0"},

"downloaded": []string{"0"},

"compact": []string{"1"},

"left": []string{strconv.Itoa(t.Length)},

}

base.RawQuery = params.Encode()

return base.String(), nil

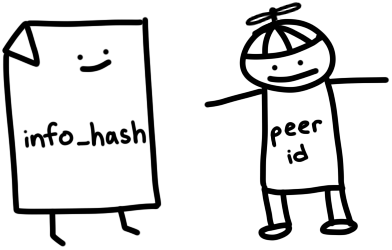

}The important ones:

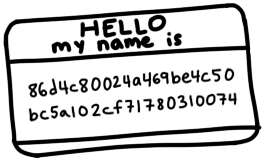

- info_hash: Identifies the file we’re trying to download. It’s the infohash we calculated earlier from the bencoded

infodict. The tracker will use this to figure out which peers to show us. - peer_id: A 20 byte name to identify ourselves to trackers and peers. We’ll just generate 20 random bytes for this. Real BitTorrent clients have IDs like

-TR2940-k8hj0wgej6chwhich identify the client software and version—in this case, TR2940 stands for Transmission client 2.94.

Parsing the tracker response

We get back a bencoded response:

d

8:interval

i900e

5:peers

252:(another long binary blob)

eInterval tells us how often we’re supposed to connect to the tracker again to refresh our list of peers. A value of 900 means we should reconnect every 15 minutes (900 seconds).

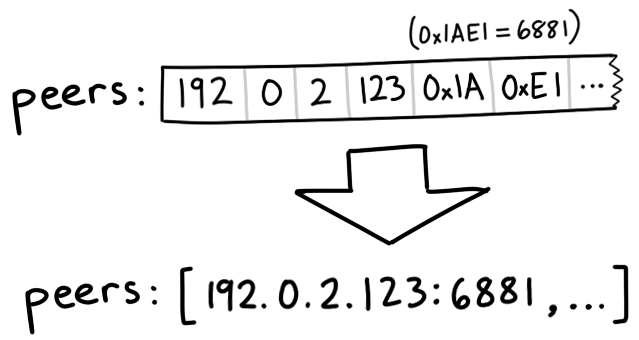

Peers is another long binary blob containing the IP addresses of each peer. It’s made out of groups of six bytes. The first four bytes in each group represent the peer’s IP address—each byte represents a number in the IP. The last two bytes represent the port, as a big-endian uint16. Big-endian, or network order, means that we can interpret a group of bytes as an integer by just squishing them together left to right. For example, the bytes 0x1A, 0xE1 make 0x1AE1, or 6881 in decimal.

// Peer encodes connection information for a peer

type Peer struct {

IP net.IP

Port uint16

}

// Unmarshal parses peer IP addresses and ports from a buffer

func Unmarshal(peersBin []byte) ([]Peer, error) {

const peerSize = 6 // 4 for IP, 2 for port

numPeers := len(peersBin) / peerSize

if len(peersBin)%peerSize != 0 {

err := fmt.Errorf("Received malformed peers")

return nil, err

}

peers := make([]Peer, numPeers)

for i := 0; i < numPeers; i++ {

offset := i * peerSize

peers[i].IP = net.IP(peersBin[offset : offset+4])

peers[i].Port = binary.BigEndian.Uint16(peersBin[offset+4 : offset+6])

}

return peers, nil

}Downloading from peers

Now that we have a list of peers, it’s time to connect with them and start downloading pieces! We can break down the process into a few steps. For each peer, we want to:

- Start a TCP connection with the peer. This is like starting a phone call.

- Complete a two-way BitTorrent handshake. “Hello?” “Hello.”

- Exchange messages to download pieces. “I’d like piece #231 please.”

Start a TCP connection

conn, err := net.DialTimeout("tcp", peer.String(), 3*time.Second)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}I set a timeout so that I don’t waste too much time on peers that aren’t going to let me connect. For the most part, it’s a pretty standard TCP connection.

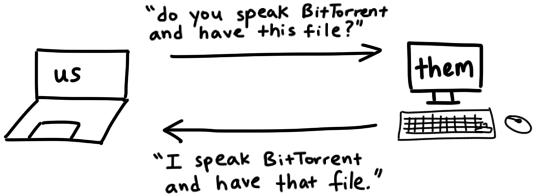

Complete the handshake

We’ve just set up a connection with a peer, but we want to do a handshake to validate our assumptions that the peer

- can communicate using the BitTorrent protocol

- is able to understand and respond to our messages

- has the file that we want, or at least knows what we’re talking about

My father told me that the secret to a good handshake is a firm grip and eye contact. The secret to a good BitTorrent handshake is that it’s made up of five parts:

- The length of the protocol identifier, which is always 19 (0x13 in hex)

- The protocol identifier, called the pstr which is always

BitTorrent protocol - Eight reserved bytes, all set to 0. We’d flip some of them to 1 to indicate that we support certain extensions. But we don’t, so we’ll keep them at 0.

- The infohash that we calculated earlier to identify which file we want

- The Peer ID that we made up to identify ourselves

Put together, a handshake string might look like this:

\x13BitTorrent protocol\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x86\xd4\xc8\x00\x24\xa4\x69\xbe\x4c\x50\xbc\x5a\x10\x2c\xf7\x17\x80\x31\x00\x74-TR2940-k8hj0wgej6chAfter we send a handshake to our peer, we should receive a handshake back in the same format. The infohash we get back should match the one we sent so that we know that we’re talking about the same file. If everything goes as planned, we’re good to go. If not, we can sever the connection because there’s something wrong. “Hello?” “这是谁? 你想要什么?” “Okay, wow, wrong number.”

In our code, let’s make a struct to represent a handshake, and write a few methods for serializing and reading them:

// A Handshake is a special message that a peer uses to identify itself

type Handshake struct {

Pstr string

InfoHash [20]byte

PeerID [20]byte

}

// Serialize serializes the handshake to a buffer

func (h *Handshake) Serialize() []byte {

buf := make([]byte, len(h.Pstr)+49)

buf[0] = byte(len(h.Pstr))

curr := 1

curr += copy(buf[curr:], h.Pstr)

curr += copy(buf[curr:], make([]byte, 8)) // 8 reserved bytes

curr += copy(buf[curr:], h.InfoHash[:])

curr += copy(buf[curr:], h.PeerID[:])

return buf

}

// Read parses a handshake from a stream

func Read(r io.Reader) (*Handshake, error) {

// Do Serialize(), but backwards

// ...

}Send and receive messages

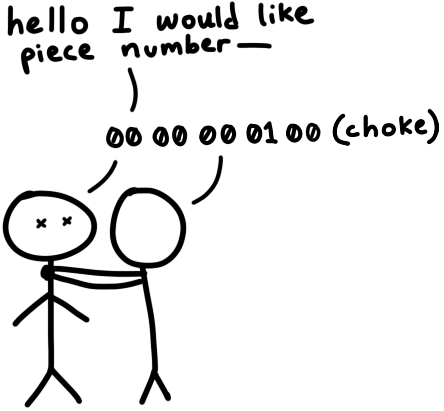

Once we’ve completed the initial handshake, we can send and receive messages. Well, not quite—if the other peer isn’t ready to accept messages, we can’t send any until they tell us they’re ready. In this state, we’re considered choked by the other peer. They’ll send us an unchoke message to let us know that we can begin asking them for data. By default, we assume that we’re choked until proven otherwise.

Once we’ve been unchoked, we can then begin sending requests for pieces, and they can send us messages back containing pieces.

Interpreting messages

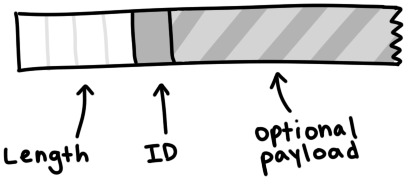

A message has a length, an ID and a payload. On the wire, it looks like:

A message starts with a length indicator which tells us how many bytes long the message will be. It’s a 32-bit integer, meaning it’s made out of four bytes smooshed together in big-endian order. The next byte, the ID, tells us which type of message we’re receiving—for example, a 2 byte means “interested.” Finally, the optional payload fills out the remaining length of the message.

type messageID uint8

const (

MsgChoke messageID = 0

MsgUnchoke messageID = 1

MsgInterested messageID = 2

MsgNotInterested messageID = 3

MsgHave messageID = 4

MsgBitfield messageID = 5

MsgRequest messageID = 6

MsgPiece messageID = 7

MsgCancel messageID = 8

)

// Message stores ID and payload of a message

type Message struct {

ID messageID

Payload []byte

}

// Serialize serializes a message into a buffer of the form

// <length prefix><message ID><payload>

// Interprets `nil` as a keep-alive message

func (m *Message) Serialize() []byte {

if m == nil {

return make([]byte, 4)

}

length := uint32(len(m.Payload) + 1) // +1 for id

buf := make([]byte, 4+length)

binary.BigEndian.PutUint32(buf[0:4], length)

buf[4] = byte(m.ID)

copy(buf[5:], m.Payload)

return buf

}To read a message from a stream, we just follow the format of a message. We read four bytes and interpret them as a uint32 to get the length of the message. Then, we read that number of bytes to get the ID (the first byte) and the payload (the remaining bytes).

// Read parses a message from a stream. Returns `nil` on keep-alive message

func Read(r io.Reader) (*Message, error) {

lengthBuf := make([]byte, 4)

_, err := io.ReadFull(r, lengthBuf)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

length := binary.BigEndian.Uint32(lengthBuf)

// keep-alive message

if length == 0 {

return nil, nil

}

messageBuf := make([]byte, length)

_, err = io.ReadFull(r, messageBuf)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

m := Message{

ID: messageID(messageBuf[0]),

Payload: messageBuf[1:],

}

return &m, nil

}Bitfields

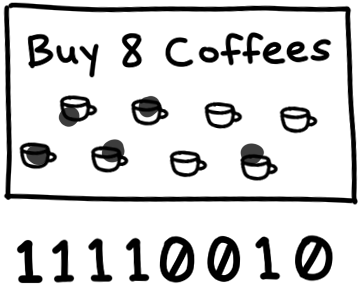

One of the most interesting types of message is the bitfield, which is a data structure that peers use to efficiently encode which pieces they are able to send us. A bitfield looks like a byte array, and to check which pieces they have, we just need to look at the positions of the bits set to 1. You can think of it like the digital equivalent of a coffee shop loyalty card. We start with a blank card of all 0, and flip bits to 1 to mark their positions as “stamped.”

By working with bits instead of bytes, this data structure is super compact. We can stuff information about eight pieces in the space of a single byte—the size of a bool. The tradeoff is that accessing values becomes a little more tricky. The smallest unit of memory that computers can address are bytes, so to get to our bits, we have to do some bitwise manipulation:

// A Bitfield represents the pieces that a peer has

type Bitfield []byte

// HasPiece tells if a bitfield has a particular index set

func (bf Bitfield) HasPiece(index int) bool {

byteIndex := index / 8

offset := index % 8

return bf[byteIndex]>>(7-offset)&1 != 0

}

// SetPiece sets a bit in the bitfield

func (bf Bitfield) SetPiece(index int) {

byteIndex := index / 8

offset := index % 8

bf[byteIndex] |= 1 << (7 - offset)

}Putting it all together

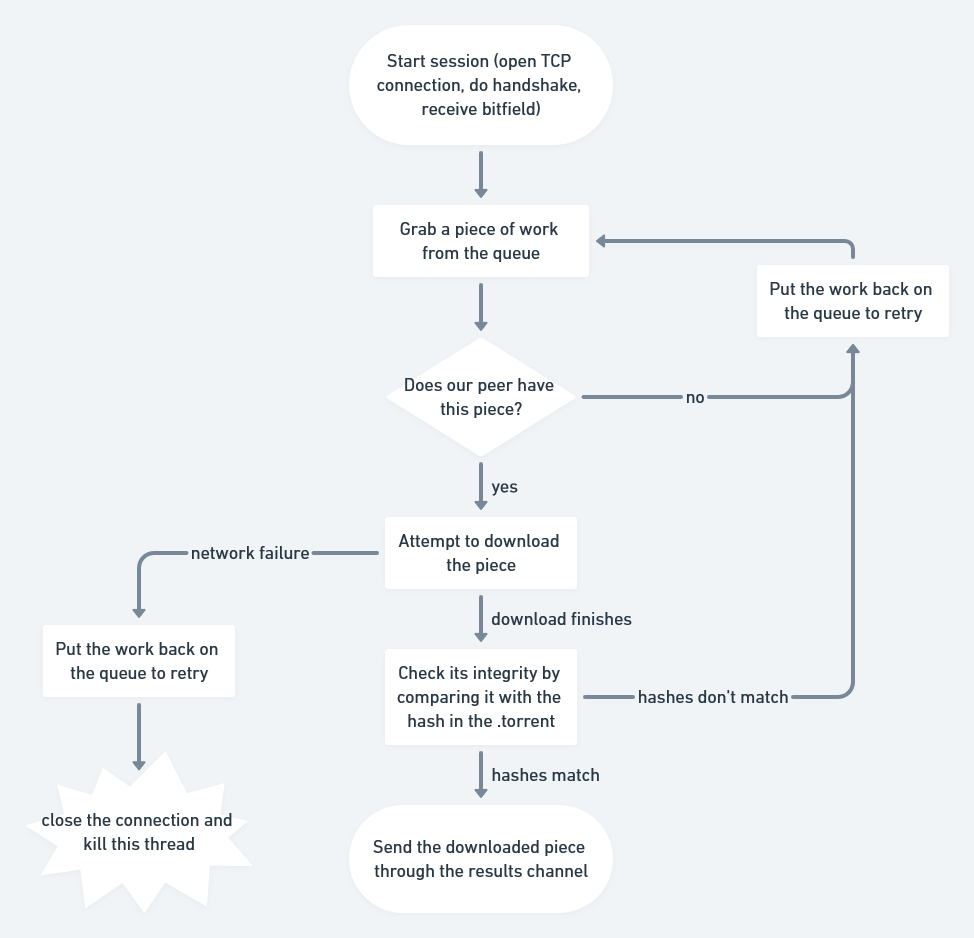

We now have all the tools we need to download a torrent: we have a list of peers obtained from the tracker, and we can communicate with them by dialing a TCP connection, initiating a handshake, and sending and receiving messages. Our last big problems are handling the concurrency involved in talking to multiple peers at once, and managing the state of our peers as we interact with them. These are both classically Hard problems.

Managing concurrency: channels as queues

In Go, we share memory by communicating, and we can think of a Go channel as a cheap thread-safe queue.

We’ll set up two channels to synchronize our concurrent workers: one for dishing out work (pieces to download) between peers, and another for collecting downloaded pieces. As downloaded pieces come in through the results channel, we can copy them into a buffer to start assembling our complete file.

// Init queues for workers to retrieve work and send results

workQueue := make(chan *pieceWork, len(t.PieceHashes))

results := make(chan *pieceResult)

for index, hash := range t.PieceHashes {

length := t.calculatePieceSize(index)

workQueue <- &pieceWork{index, hash, length}

}

// Start workers

for _, peer := range t.Peers {

go t.startDownloadWorker(peer, workQueue, results)

}

// Collect results into a buffer until full

buf := make([]byte, t.Length)

donePieces := 0

for donePieces < len(t.PieceHashes) {

res := <-results

begin, end := t.calculateBoundsForPiece(res.index)

copy(buf[begin:end], res.buf)

donePieces++

}

close(workQueue)We’ll spawn a worker goroutine for each peer we’ve received from the tracker. It’ll connect and handshake with the peer, and then start retrieving work from the workQueue, attempting to download it, and sending downloaded pieces back through the results channel.

func (t *Torrent) startDownloadWorker(peer peers.Peer, workQueue chan *pieceWork, results chan *pieceResult) {

c, err := client.New(peer, t.PeerID, t.InfoHash)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Could not handshake with %s. Disconnecting\n", peer.IP)

return

}

defer c.Conn.Close()

log.Printf("Completed handshake with %s\n", peer.IP)

c.SendUnchoke()

c.SendInterested()

for pw := range workQueue {

if !c.Bitfield.HasPiece(pw.index) {

workQueue <- pw // Put piece back on the queue

continue

}

// Download the piece

buf, err := attemptDownloadPiece(c, pw)

if err != nil {

log.Println("Exiting", err)

workQueue <- pw // Put piece back on the queue

return

}

err = checkIntegrity(pw, buf)

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Piece #%d failed integrity check\n", pw.index)

workQueue <- pw // Put piece back on the queue

continue

}

c.SendHave(pw.index)

results <- &pieceResult{pw.index, buf}

}

}Managing state

We’ll keep track of each peer in a struct, and modify that struct as we read messages. It’ll include data like how much we’ve downloaded from the peer, how much we’ve requested from them, and whether we’re choked. If we wanted to scale this further, we could formalize this as a finite state machine. But a struct and a switch are good enough for now.

type pieceProgress struct {

index int

client *client.Client

buf []byte

downloaded int

requested int

backlog int

}

func (state *pieceProgress) readMessage() error {

msg, err := state.client.Read() // this call blocks

switch msg.ID {

case message.MsgUnchoke:

state.client.Choked = false

case message.MsgChoke:

state.client.Choked = true

case message.MsgHave:

index, err := message.ParseHave(msg)

state.client.Bitfield.SetPiece(index)

case message.MsgPiece:

n, err := message.ParsePiece(state.index, state.buf, msg)

state.downloaded += n

state.backlog--

}

return nil

}Time to make requests!

Files, pieces, and piece hashes aren’t the full story—we can go further by breaking down pieces into blocks. A block is a part of a piece, and we can fully define a block by the index of the piece it’s part of, its byte offset within the piece, and its length. When we make requests for data from peers, we are actually requesting blocks. A block is usually 16KB large, meaning that a single 256 KB piece might actually require 16 requests.

A peer is supposed to sever the connection if they receive a request for a block larger than 16KB. However, based on my experience, they’re often perfectly happy to satisfy requests up to 128KB. I only got moderate gains in overall speed with larger block sizes, so it’s probably better to stick with the spec.

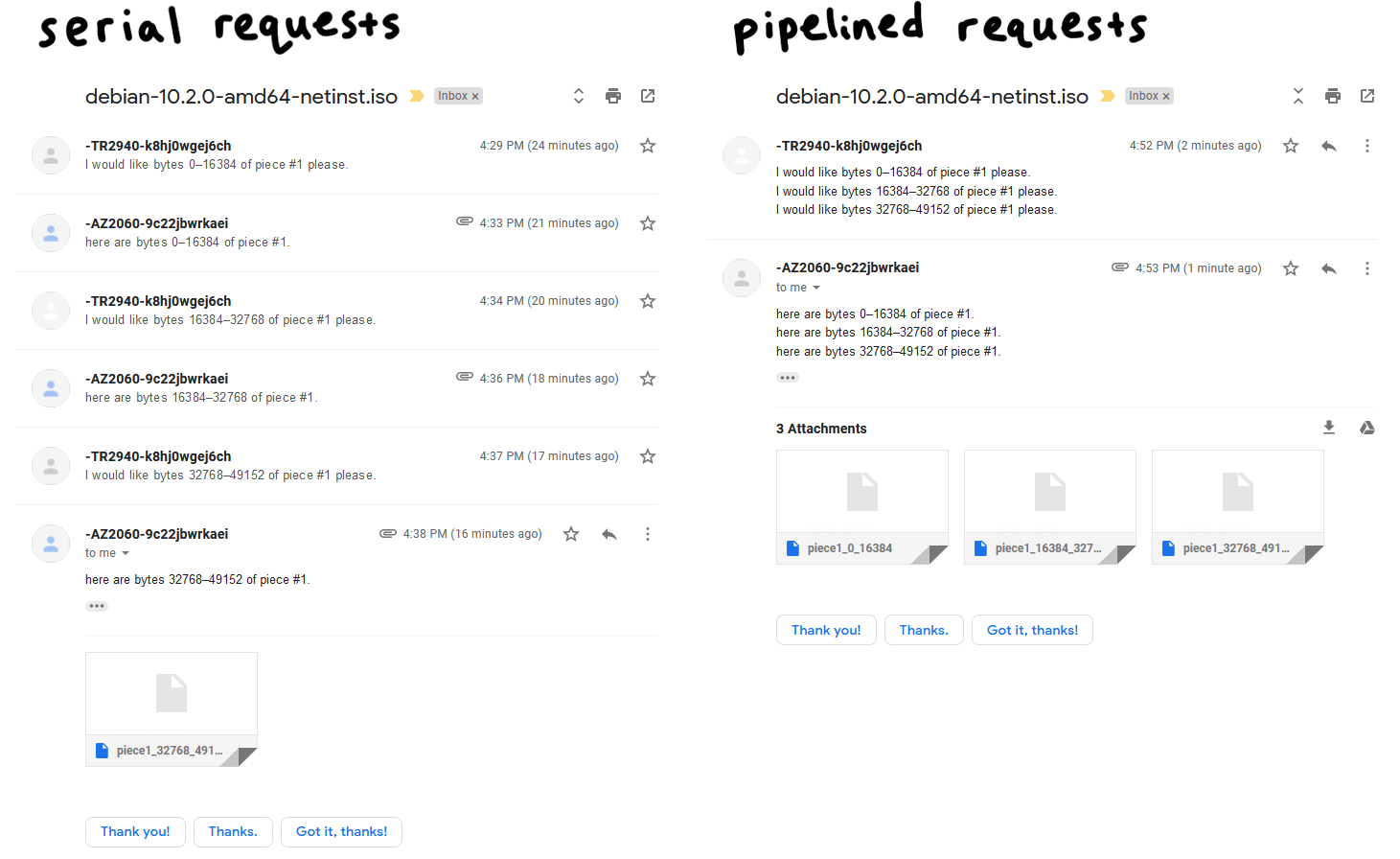

Pipelining

Network round-trips are expensive, and requesting each block one by one will absolutely thank the performance of our download. Therefore, it’s important to pipeline our requests such that we keep up a constant pressure of some number of unfulfilled requests. This can increase the throughput of our connection by an order of magnitude.

Classically, BitTorrent clients kept a queue of five pipelined requests, and that’s the value I’ll be using. I found that increasing it can up to double the speed of a download. Newer clients use an adaptive queue size to better accommodate modern network speeds and conditions. This is definitely a parameter worth tweaking, and it’s pretty low hanging fruit for future performance optimization.

// MaxBlockSize is the largest number of bytes a request can ask for

const MaxBlockSize = 16384

// MaxBacklog is the number of unfulfilled requests a client can have in its pipeline

const MaxBacklog = 5

func attemptDownloadPiece(c *client.Client, pw *pieceWork) ([]byte, error) {

state := pieceProgress{

index: pw.index,

client: c,

buf: make([]byte, pw.length),

}

// Setting a deadline helps get unresponsive peers unstuck.

// 30 seconds is more than enough time to download a 262 KB piece

c.Conn.SetDeadline(time.Now().Add(30 * time.Second))

defer c.Conn.SetDeadline(time.Time{}) // Disable the deadline

for state.downloaded < pw.length {

// If unchoked, send requests until we have enough unfulfilled requests

if !state.client.Choked {

for state.backlog < MaxBacklog && state.requested < pw.length {

blockSize := MaxBlockSize

// Last block might be shorter than the typical block

if pw.length-state.requested < blockSize {

blockSize = pw.length - state.requested

}

err := c.SendRequest(pw.index, state.requested, blockSize)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

state.backlog++

state.requested += blockSize

}

}

err := state.readMessage()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

}

return state.buf, nil

}main.go

This is a short one. We’re almost there.

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

"github.com/veggiedefender/torrent-client/torrentfile"

)

func main() {

inPath := os.Args[1]

outPath := os.Args[2]

tf, err := torrentfile.Open(inPath)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

err = tf.DownloadToFile(outPath)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

}This isn’t the full story

For brevity, I included only a few of the important snippets of code. Notably, I left out all the glue code, parsing, unit tests, and the boring parts that build character. View my full implementation if you’re interested.

Jesse Li

Jesse Li